La guerra entre bacterias y hongos que ocurre en la endósfera de raíz, favorece el crecimiento de las plantas

La microbiota de raíz está compuesta por diversos grupos de microorganismos, como las bacterias, los hongos y los protistas. Con el objetivo de entender éstas interacciones, el presente trabajo de Durán y colaboradores, analizó la diversidad de dichos grupos en raíces de Arabidopsis thaliana por medio de amplicones del gen 16S rRNA en bacterias y de ITS en hongos y protistas (oomycetes). En ésta primera etapa del proyecto, encontraron diferencias en las comunidades de bacterias y hongos, relacionadas con el tipo muestra (suelo, episfera y endósfera) y con la localidad de colecta. De manera general, las comunidades de bacterias están domindadas por Chloroflexi y Proteobacteria; las de hongos por Acomycota y Basidiomycota; y las de oomyctes por Pythiales.

Figure 1: Microbial community structure in three natural A. thaliana populations. a, Relative abundance of bacterial, fungal and oomycetal taxa in soil, root episphere and root endosphere compartments in three sites (Pulheim and Geyen in Germany and Saint-Dié in France). The taxonomic assignment is based on the RDP using a bootstrap cutoff of 0.5%. Low- abundance taxonomic groups with less than 0.5% of total reads across all samples are highlighted in black. Each technical replicate comprised a pool of four plants. b, Relative abundance (RA) of OTUs significantly enriched in a specific site or compartment. A generalized linear model was used to compare OTU abundance profiles in one site or compartment versus the other two sites or compartments, respectively (p < 0.05, FDR corrected). The relative abundances for these OTUs were aggregated at the class level. c, Community structure of bacteria, fungi and oomycetes in the 36 samples was determined using principal component analysis. The first two dimensions of a principal component analysis are plotted based on Bray-Curtis distances. Samples are colour-coded according to the compartment and sites are depicted with different symbols.

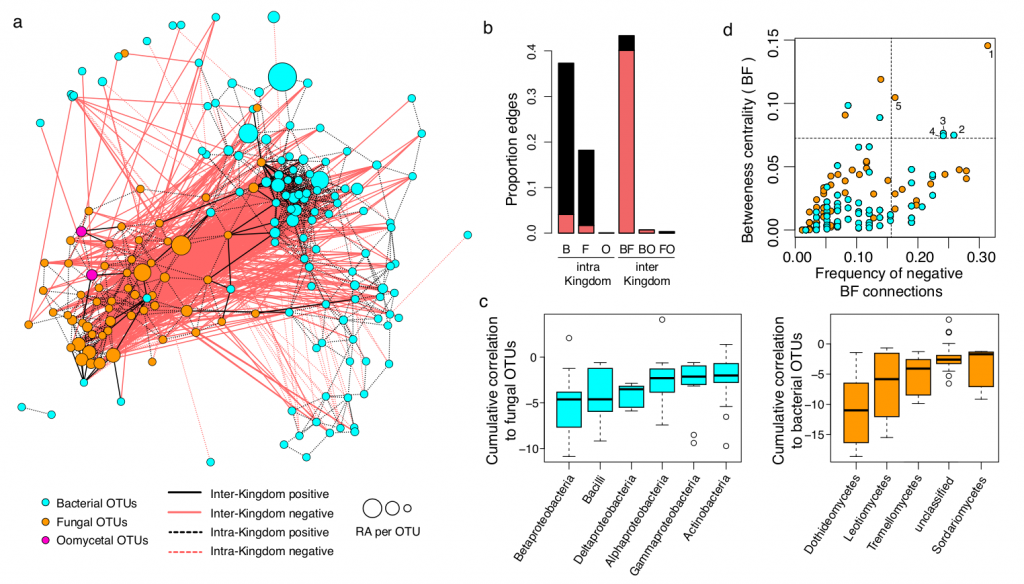

Para explorar las interacciones los reinos de bacterias, hongos y protistas, crearon redes de co-ocurrencia (por medio de correlaciones), en las que se muestran interacciones tanto positivas como negativas. En todos los casos las interacciones intra-reino son positivas; mientras que las interacciones entre los reinos son negativas, sobre todo entre hongos y bacterias. La centralidad de intermediación es una medida de los nodos de las redes que indica que tantas conexiones utilizan como intermediario a un nodo determinado. Considerando que cada nodo observado en la red corresponde a un OTU, se correlacionó la centralidad de intermediación de los nodos con la frecuencia de conexiones negativas con otros nodos, para detectar OTUs de gran importancia que fueran antagonistas, tanto de hongos como de bacterias. Los cinco OTUs que destacaron en la interacción corresponden a bacterias Betaproteobacterias, Bacilos y Deltaproteobacterias; y a hongos Dothidomycetes, Leotiomycetes y Tremellomycetes.

Figure 2: Microbial network of the A. thaliana root endosphere microbiota. a, Correlation-based network of root-associated microbial OTUs detected in three natural A. thaliana populations (Pulheim, Geyen, Saint-Dié). Each node corresponds to an OTU and edges between nodes correspond to either positive (black) or negative (red) correlations inferred from OTU abundance profiles using the SparCC method (pseudo p-value >0.05, correlation values <-0.6 or >0.6). OTUs belonging to different microbial kingdoms have distinct colour codes and node size reflects their relative abundance (RA) in the root endosphere compartment. Intra-kingdom correlations are represented with dotted lines and inter-kingdom correlations by solid lines. b, Proportion of edges showing positive (black) or negative (red) correlations in the microbial root endosphere network. B: bacteria, F: fungi, O: oomycetes. c, Cumulative correlation scores measured in the microbial network between bacterial and fungal OTUs. Bacterial (left) and fungal (right) OTUs were grouped at the class level (> five OTUs/class) and sorted according to their cumulative correlation scores with fungal and bacterial OTUs, respectively. d, Hub properties of negatively correlated bacterial and fungal OTUs. For each fungal and bacterial OTU, the frequency of negative inter- kingdom connections is plotted against the betweenness centrality inferred from all negative BF connections (cases in which a node lies on the shortest path between all pairs of other nodes). The five microbial OTUs that show a high frequency of negative inter-kingdom connections and betweenness centrality scores represent hubs of the “antagonistic” network and are highlighted with numbers. 1: Davidiella; 2: Variovorax; 3: Kineosporia; 4: Acidovorax; 5: Alternaria

La siguiente fase del experimento, consistió en establecer la manera en la que dichas interacciones afectan la salud de las plantas. Para ello, se aislaron bacterias de la raíz de A. thaliana y comprobaron (por medio de la secuenciacón de los aislados), que se recuperaban la mayoría de los OTUs con alta abundancia. Después de aislarlos, se crearon comunidades artificiales de bacterias, hongos y oomycetes que inocularon a plantas de A. thaliana crecidas en sustrato estéril en un experimento de jardín común. Posteriormente se analizó el peso fresco de las plantas, crecidas con las siguientes comunidades de microorganismos: un control libre de microbios, bacterias, hongos, oomycetes, bacterias con oomycetos, bacterias con hongos, hongos con oomycetos y los tres taxa juntos. De manera notable, las muestras del control negativo mostraron valores bajos de biomasa, pero las crecidas con hongos u hongos con oomycetes, murieron. Los valores más altos de biomasa se observaron en la comunidad de bacterias, hongos y oomycetes, seguidas por la comunidad compuesta únicamente por bacterias.

Figure 4: Multi-kingdom reconstitution of the A. thaliana root microbiota. a, Re- colonization of germ-free plants with root-derived bacterial (148), fungal (34) and oomycetal (9) isolates in the FlowPot system. Shoot fresh weight of four-week-old A. thaliana Col-0 inoculated with bacteria (B), fungi (F), oomycetes (O) bacteria and oomycetes (BO), bacteria and fungi (BF), fungi and oomycetes (FO) and bacteria, fungi and oomycetes (BFO). MF: microbe-free/control. Shoot fresh weight values were normalized to MF. Significant differences are depicted with letters (p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s post-hoc tests). Survival rate values represent the percentage of germinated plants that survived. Data are from three biological replicates (represented by different shapes) with three technical replicates each. b, Observed species per microbial group in matrix samples for each of the above-mentioned inoculations (p<0.05, Kruskal Wallis and Dunn’s post-hoc tests). Input: initial microbial inoculum. UNPL: unplanted matrix. c, Relative abundances of microbial isolates in initial input and output matrix and root samples after four weeks. Taxonomic assignment is shown at the phylum level for bacteria and at the species level for fungi and oomycetes. Numbers in brackets refer to enriched species in Figure S11B.

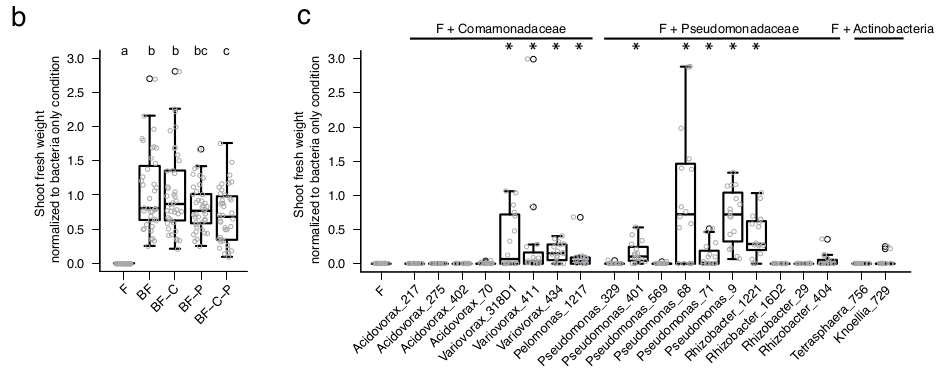

Esporas de hongos del experimento anterior, fueron tomadas y colocadas en placas con medio TSB, que se utilizaron para probar 2,862 interacciones binarias, en las que se midió la manera en la que las bacterias influyen en el crecimiento de los hongos. Las interacciones mostraron una señal filogenética clara en la que las familias Comamonadaceae y Pseudomonadaceae, que tienen un efecto negativo muy marcado en el crecimiento de los hongos. Por lo anterior, volvieron a realizar experimentos de jardín común, en los que se probó lo que ocurría cuando se eliminaban Comamonadaceae y Pseudomonadaceae de los inóculos, lo cual resultó en una disminución de la biomasa de las plantas. Finalmente, se inocularon asilados de manera individual y se observó que algunos géneros como Variovorax, Pseudomonas o Rhizobacter (que pertenecen a las familias identificadas con antagonistas fúngicos), son capaces de favorecer el crecimiento de las plantas.

(presence vs. absence of bacterial competitors) measured by fluorescence using a chitin binding assay against Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated WGA. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the full bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences and bootstrap values are depicted with black circles. Vertical and horizontal barplots indicate the cumulative antagonistic activity for each bacterial strain and the cumulative sensitivity score for each fungal isolate, respectively. Alternating white and black colours are used to distinguish the bacterial families. All bacteria presented and 7/27 fungi (highlighted in bold) were used for the above-mentioned multi-kingdom reconstitution experiment (see Figure 4). b, Shoot fresh weight of fungi and bacteria-inoculated plants relative to the bacteria-only inoculated plants in depletion experiments, in which specific bacterial families (C: Commonadaceae; P: Pseudomonadaceae) were removed to test their fungal control capacity. Significant differences are depicted with letters (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc test, p<0.05). c, Same experiment as in b, but instead of depleting strains, single bacterial isolates were co- inoculated with the 34-member fungal community (F) to test their plant growth rescue activities.

Referencia:

Duran, P., Thiergart, T., Garrido-Oter, R., Agler, M., Kemen, E., Schulze-Lefert, P., & Hacquard, S. (2018). Microbial interkingdom interactions in roots promote Arabidopsis survival. bioRxiv, 354167.